The tide is turning against the RBA, with more and more economists starting to think they’ve got it badly wrong.

Headline inflation is back in the target range, underlying inflation is moving ever closer to target, and yet the Reserve Bank of Australia remains stone-faced, the monolith of Martin Place. The RBA says it can’t cut rates, not yet. Not with unemployment so low.

The idea is that if there is an economy-wide shortage of workers then it’s a zero-sum game. Businesses that lose workers to businesses paying higher wages will, in turn, bid up wages to fill their vacant positions. The result is rapidly rising wages. These higher wages eat into the profits of businesses, so businesses use their market power to put up their prices which causes inflation.

This is known as a wage-price spiral. Simply put, the RBA believes low unemployment leads to higher inflation.

The RBA reckons we need unemployment to rise to somewhere around 4.5 per cent from where it is now. That would mean tens of thousands more people looking for work. Not a pleasant prospect.

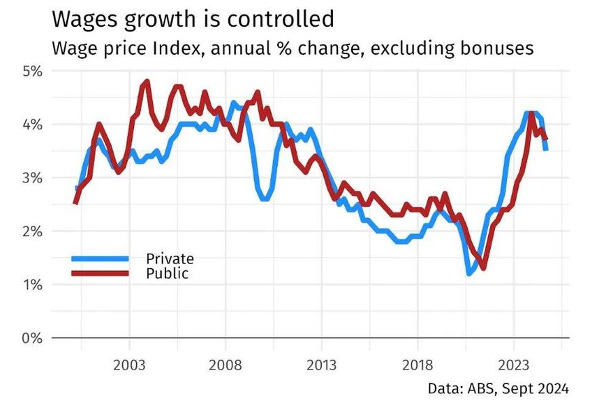

However, the unemployment rate has tracked sideways at around 4.1% for the past 6 months and the inflation rate has been tracking downward during this period. Wages growth is already falling and it’s wages growth that is really the feedback loop from low unemployment to high inflation.

It can also be argued that the RBA estimate of how low unemployment needs to be to set off a wage-price spiral is wrong. The RBA Review released in 2023 pointed out the errors in this thinking pre-Covid. The RBA is repeating its mistakes now. Wage growth is falling, GDP per capita is 2.5% below the long-term trend – only being held at that level due to government spending on infrastructure, and household consumption is back to 2018 levels.

Interest rates have sat at 4.35% now for more than a year as inflation has fallen. As always, the rate rises took a few months to have their impact, but right now they are smashing the economy. The next RBA Board meeting is not until mid-February. Hopefully the data the RBA gets then opens the way to rate cuts earlier rather than later.